We thought it might be helpful to those of you interested in eating

more local-organically to tell you about what our diet looks like. Our

goal is to eat as much from local-organic sources as possible. That

means we mainly eat from our own farm, but we also

buy/barter/forage/hunt/scavenge other local-organic foods, and

compromise on just a few foods we feel like we haven't figured out yet:

oats, millet, oil, vinegar -- we buy those things from USDA organic

sources -- and very rarely some wild fish. We also buy salt, baking

soda, and some spices, although we're fairly content with those food

purchases. For our young family of six we spend well under $1000 per

year on food, which includes the local-organic foods we buy (pecans are a big one in the years we can find them), which we say just to put how

much we're eating from our own farm and other non-purchased sources in

perspective.

Millet might seem like an odd thing to keep buying when we've let go

of rice but a big part of the reason we started eating millet was

because we wanted to begin by learning how to enjoy the foods that we

aspired to grow. It's a minor grain for us, but eating millet is for us a very small

step towards growing millet. Our most important grains,

though, are the corn and wheat we grow ourselves, along with non-local

purchased oats [as of 2019, growing some but still far from all of our own oats.] We use wheat mainly

for bread, pancakes, pizza, biscuits, in lesser amounts in desserts and

sauces, and occasionally in pasta, but homemade pasta is time-consuming

enough that we don't eat pasta very often. We use corn mainly as

cornmeal and grits for cornbread/muffins, corn mush (for breakfast),

grits and fried grits (for breakfast but more often as a starch/grain to

go with a main meal), cornmeal casseroles, cornmeal pancakes, and, when

we have enough lard, as hush puppies. We also make hominy from our

corn, which we mainly use whole mixed with vegetables or beans like

pintos, but we also really enjoy tortillas made from grinding fresh

hominy, but as with pasta, that feels too time-consuming to do on a

weekly basis (even though lots of central Americans do it daily.)

[As of 2019, we're eating tortillas much more often. Mostly we've just gotten in the habit, but we also bought a tortilla press which makes that one step of the process significantly faster.] Buckwheat is the other grain we grow for ourselves, and so far pancakes

are about the only thing we've made with buckwheat flour, which,

however, we really enjoy, commonly with sorghum syrup, that we get from

neighbor-friends.

Although eating local-organically means we don't eat anything like

granulated sugar or brown sugar, we do eat plenty of sweeteners. We'll

eat some sorghum syrup on bread or biscuits, in addition to our standard

buckwheat pancakes, and we'll buy a little bit of maple syrup when we're

visiting Melissa's family in Michigan, but we mainly eat lots of honey,

about a quart per week. If we eat ice cream, it's sweetened with honey,

either as just plain honey ice cream or flavored with black walnuts or

strawberries or mint... If we bake a pie or a persimmon pudding or a

custard (like flan) those things are all sweetened with honey. Of

course, we also use honey for the more obvious uses of sweetening tea

(which for us mostly means mint or roselle) and on toast and biscuits.

We particularly like creamed honey on biscuits. Perhaps our biggest use

of honey, though, is with yogurt. Yogurt and honey, often without

anything else, but sometimes with fruit or pecans or granola... is one

of our most common afternoon snacks as well as a fairly common

breakfast. [As of 2019, we're harvesting a lot more fruit than we were before, so we're eating more fruit and less honey these days, although we still probably use at least a pint per week.] Popcorn and peanuts, boiled when we're digging them fresh and

roasted the rest of the year, are our other two main snack foods.

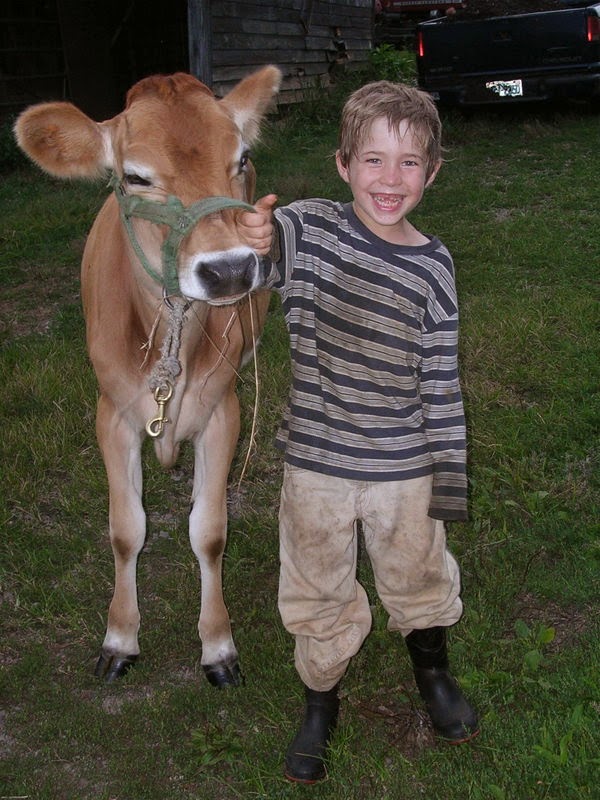

Dairy is probably our most important protein

source. As with the rest of our diet, that's not determined by any

health theories or taste preferences so much as the simple fact of what

our farm can most efficiently produce. (We believe that eating whatever

our farm can produce is, however, leading us to food that's healthier

and tastier than anything we could buy.) Most of our farm is too

rolling to be suitable for us to use for anything other than woods or

pasture, and dairy seems to be the best way we can eat grass, which is

an outstanding crop in terms of sustainability anyways. We eat a lot of yogurt, probably over two gallons per week, some

weeks maybe three. In addition to

yogurt, we drink two or three gallons of milk each week, plus what we

use in cooking. And we make a few simple cheeses. We make pretty much

all of our goat's milk into a simple, soft cheese. With cow's milk we

make cottage cheese, mozzarella, and ricotta. We would certainly enjoy

hard/aged cheese, but we need to build a press and construct some kind

of "cave" (aging room/space) first, and we haven't made that happen yet,

so we do without hard cheeses in the meantime. Most of the milk we

drink and most of the things we make from milk are made from skimmed

milk -- we simply ladle the cream off the top with a measuring cup, so

our skimmed milk still has a decent amount of fat left -- because butter

is our first priority for the cream. Even with rich Jersey milk, it

probably takes four gallons or more of milk to make a pound of butter.

Butter is the most efficient local-organic fat we can produce (because

it's made mainly of permanent pasture that the cows harvest for

themselves), but butter is only efficient so long as we're able to

realize substantial value from all the gallons of skimmed milk that

comes with every pound of butter. Still, hand milking a cow to make

butter is no way to compete with supermarket prices.

Other fats (lard and oil) are even more costly. Our supply of lard

is limited by our supply of hog feed. Although swine are great at

making use of various farm and kitchen byproducts and surpluses, we

haven't had enough of these things to be able to do without substantial

quantities of crops grown and harvested particularly for feed,

especially not year-round and for the full life and breeding cycle, so

we use butter for a lot of uses we might otherwise use lard. [As of 2019 after two or three more rounds of raising hogs, pork and lard are seeming a little more promising and efficient.] We still

buy oil, however, to make salad dressing and mayonnaise. Birds seem to

make sunflowers too difficult to try to grow for oil on any scale we could grow them, but we're

currently trying to figure out how to grow significant quantities of

sesame seeds. Of course, if we can grow enough seeds, we'd still need

an oil press, but growing the seeds seems like the most challenging

hurdle to local-organic salad oil. [As of 2019, we've made some progress toward growing enough sesame seeds for oil, but still have a ways to go. In the meantime, we've found some ways that we really enjoy for substituting cream or bacon fat for oil, so the challenge of growing our own oil seeds has also come down a little closer.]

At least as important to our diet as anything we've discussed so

far, however, are all the vegetables we grow. We frequently eat meals

that consist primarily of vegetables, especially counting starches like

sweet potatoes and Irish potatoes as vegetables. Perhaps we wouldn't eat

quite so many vegetables if there weren't always extra vegetables that

we were bringing home from the farmers' market, but there are other

vegetables we enjoy so much that we'll only sell them after we're sure

we have enough for ourselves. Homegrown hand-picked vegetables just

offer so much great taste and variety of tastes, and there are very few

vegetables that simply won't grow well in our location and without

chemical inputs. So we eat a lot of vegetables, often in very simple

preparations: boiled butterbeans, whole roasted Asian eggplants, tomato

sandwiches, lettuce salad, boiled "green" peanuts, etc. We also eat a

lot of stir-fries, simply chopping up whatever is in season and

stir-frying it together. We've joked that stir-fries are actually all we eat: either a standard stir-fry on top of millet or fried grits,

or the topping for a pizza, or the filling for an omelette, etc.

Fruit is more limited for us than vegetables (by what's locally and

organically practical and by the fact that most fruits take years to

reach bearing age whereas most vegetables only take a year to do

everything they're ever going to do [as of 2019 we're making a lot of progress in this respect]), but we still probably enjoy a

greater variety of fruits than most people, some excellent quality

fruits like figs or satsumas (a citrus fruit similar to clementines or

tangerines) and other lesser fruits like azaroles (an edible hawthorn)

or tiny wild-type strawberries. We've eaten fresh regular (fuzzy) kiwis

as late as March, and we often get our first strawberries in April, so

we eat most of our fruit fresh, but we also freeze a lot of blueberries,

blackberries, and strawberries to eat throughout the year, as well as

persimmon pulp (mostly for puddings) and cantaloupe puree (mainly for

ice cream -- if it doesn't sound really good, try it!) We dry Asian

pears and figs. Drying Asian pears doesn't have much preserving value

for us, because dried Asian pears mostly get eaten before the fresh

fruit would have gone bad, but most years we manage to dry a good number

of figs, and they're our primary dried fruit, which we use in most

things that might otherwise contain raisins: on salads, in oatmeal, and

as a straight up snack.

[As of 2019, most of the above crops, as well as mulberries, muscadine grapes, Asian persimmons, jujubes, pawpaws, hardy (small, without fuzz) kiwis, and other fruits are trending toward significantly more plentiful crops, although there are lots of year-to-year ups and downs with fruit crops.]

Roselle isn't a fruit -- it's technically a flower part -- but we

use it as a cranberry substitute, which once cooked very closely

resembles cranberry sauce. Besides as a sauce to go with yogurt or

desserts or meat/poultry, we make a lot of roselle tea. We haven't

found fruit juices very doable local-organically, although we

occasionally find some cider to drink. We've made mead (honey "wine")

since before we ever started farming. That's a simple if slow process.

We've grown barley and hops with aspirations of making beer but that

whole process is pretty complicated, and we've been more motivated to

pursue other things lately. Of course, we don't grow coffee -- there

are some non-caffeinated coffee substitutes we could make, but we were

never much into regular coffee -- but we do grow true (Chinese type)

tea, although that's another crop that we haven't yet really figured out how to

use, particularly not the fermentation process of turning fresh tea

leaves into black tea.

[As of 2019, we're making about half of a generous personal supply of our own black tea from our tea bush, and we're propagating more tea bushes to be able to increase our production further.]

We eat plenty of eggs, although our free range flock is pretty

seasonal, so some seasons are full of omelettes and flan and whole wheat

angel food cake (although that may be an oxymoron) and other seasons we

ration our egg consumption tightly.

Beef and veal (by which we simply mean beef butchered while it's

still drinking milk and hardly eating any grass yet) are our main

sources of meat besides game, especially deer meat, but also the

occasional rabbit or wild turkey. We eat much less chicken than most

Americans nowadays. We don't eat a lot of pork but we put a little bit

of cured pork or fatback in a lot of things. After hesitating for too

long, we finally realized we love young goat meat, which is tender and

very mild flavored, but our young dairy breed goats aren't very big (especially at the age we'd otherwise wean them, which makes for a good time to butcher them), so

a young goat typically only makes a few main meals with leftovers. We'd like to increase the size of our goat herd, but

parasitic worms make higher stocking densities challenging in organic

systems in our climate.

We eat a variety of dry field peas (most of the same peas we harvest

as fresh shelling peas except left to dry on the plant) as well as

October beans, pinto beans, and black beans. We tried chickpeas a time

or two without any success. Besides the field peas, October beans are

perhaps our most productive dry bean, and we really like them, so we

grow more of them than other types. There's a lot of work to harvesting

and shelling dry beans, besides all the work of growing them, so they're

not something we eat multiple times per week, but we do enjoy them

somewhat regularly.

[2019: We've made progress with dry peas and beans and have even sold some as Full Farm CSA component shares.]

Our own peanuts (boiled, roasted, or occasionally fried as a topping for stir-fries), black walnuts (mostly in smaller quantities for flavoring and a little crunch), and chestnuts (mostly roasted and eaten straight up), are the most regular and significant nuts in our diet.

This isn't a diet we sought out; it's what following local-organic

ways of farming led us to. In a lot of ways it's very similar to the

way people in this region would have eaten three or four generations

ago. A goal next year is

to produce some local-organic soy sauce to add to our diet, especially

for deer jerky. [2019: we have soybeans in storage that we might get around to experimenting with fermenting for sauce this winter.]

Our leading goal for the CSA, by the way, is to find people interested in eating (and cooking and preserving, etc.) much like we do and to then work together, starting with the Vegetable CSA and building onto that with what we call the Full Farm CSA to provide as many things as possible to our CSA members that we're growing for ourselves.

Saturday, November 15, 2014

Friday, October 31, 2014

IN PRAISE OF PUMPKINS

It all started with enough seeds to fit in a self addressed stamped

envelope. He was a retiring gardener. For forty years, he'd grown

pumpkins, saving seed. Now, on Craigslist, he was hoping to find other

gardeners to grow the pumpkins, to enjoy what he'd enjoyed. He'd

propagated something good and he wanted to share. About 50 seeds came in

the mail. Just normal looking pumpkin seeds from the man in Woodleaf;

we called them Cranford pumpkins after him. We planted out about 25

seeds in the back field. They grew vigorous from the start. We rescued

them once from Johnson grass and morning glory, but maybe they would

have thrived anyway. The vines crept out of their assigned space,

hungry for sunlight and nutrients. The leaves were wide, the vines

thick. It was impressive. But it seemed like all we were growing for

most of the summer was huge plants! Then we watched as little green

balls started to swell. As the field was in the back, we didn't check

it often. But when we did it was fun to be startled, to peak under the

leaf canopy and find growing pumpkins. We started craving pumpkin pie

in August. And then some finally began to orange, to color with

ripeness, readiness. We harvested a truck load, realizing they were as

heavy as they were big. The market scales read 40 lbs over and over.

We stored them on our front porch, we look like the most fall festive

house in the neighborhood. But the real excitement came when we cut the

first one open. The cross section revealed 2-3 inch thick bright orange

flesh. Nora grabbed the seeds for roasted pumpkin seeds (I reminded her

we can't cook them all or we won't have any pumpkins next year!) I laid

the two halves face down on cookie sheets and put them in the oven at

325. It took more than a couple hours for the monster to start to

collapse, the cookie sheet filling with water. I dumped the water out

and baked until the flesh felt soft. I flipped the halves upward and

couldn't resist tasting a a hot spoonful. It reminded me of butternut

squash. We've since been using it as a side dish at the table, simply

seasoned with some salt and butter. Pumpkin pie was expected though.

Three pies came out of the oven and was barely enough to feed the greedy

family. We've also made pumpkin bread and pumpkin pancakes. But one

can only eat so much pumpkin at a time, no matter how good. So we've

been preserving the pulp, freezing and canning, promises of pies yet to

come. Sadly, that same pickle worm that put an early end to our summer

squash migrated next to the pumpkin patch. Mighty monsters deflated out

in the field before we realized the worms internal damage were rotting

them from the inside. So upon seeing the tell tale sign of little holes

on some of the pumpkin's surface, we made good use of these doomed

pumpkins. Have you ever seen a pig go at a pumpkin? Our hog is a happy

pumpkin fed hog these days. But most of the pumpkins are fine and ready

for you to enjoy. While they are beautiful to look at it, we highly

recommend them for their culinary value as well. Looking out at my

porch these days, I'm humbled by what came of some seeds that showed up

in the mail. Less than an ounce of seeds grew to almost a ton of

pumpkin! Give thanks with us for the abundance of the season!

Tuesday, October 28, 2014

Why the CSA model?

Whether you're a member of our CSA already or whether you don't even know what a CSA is -- you can find the answer to that question here -- we'd like you to consider today some of the most important reasons we value the CSA model. We hope to increase the value you place on partnering with a particular farm that you can get to know and trust such that the way you eat is defined primarily by what comes from that kind of farming. Getting to know people that you can trust that work the land to produce the things you need is at the heart of what we think a CSA ought to be all about.

The opposite of getting food produced by people you know and trust would normally be the kind of food sold in supermarkets. Whether you actually buy it at the supermarket or elsewhere, this is pretty much complete mystery agriculture. You might sometimes have some information about the country of origin, and in those instances you could find out what laws and regulations farmers were supposed to comply with in that country, but even then you're only dealing with extremely limited minimum standards. And since there are so many details you don't know about, and since the farmers really have no means of communicating any of those differentiating details to you, the law of competition pretty much guarantees that all those details will be decided on cost, i.e. the cheapest way to produce that item will prevail. Of course, cheap is a good thing, but there are lots of things that get sacrificed for cheapness, and the supermarket model is pretty helpless to let farmers or consumers make choices about what's worth sacrificing and what isn't. For the sake of cheapness chemical fertilizers are produced from non-renewable sources (mining, fracking, etc.), displacing organic wastes that are now concentrated to the point of pollution in waterways and elsewhere. For the sake of cheapness most of the farm work in our country is structured into jobs that we would never consider fit for any of our own children but only for an immigrant underclass. (Only 18% of farm workers in the US speak English as their first language.) For the sake of cheapness highly erodible soils that ought to be protected by permanent stands of trees and grass are bulldozed and plowed to produce cheap (in the very short term) annual crops. For the sake of cheapness, fruits are picked under-ripe thousand of miles away. For the sake of cheapness pesticides are sprayed on crops that correlate with behavioral and mental disorders in children, contaminate drinking water sources, correlate with higher incidents of cancer, etc. And on top of that, those same pesticides sprayed on one crop destroy honeybee and native pollinator populations, increasing the cost of producing many other crops. (Cheapness often isn't really cheap even in the short run.)

Whole books could be filled and many have detailing these sorts of agricultural issues, but our point here isn't that any of these issues ought to be decided one way or another. Our point is merely that there are questions worth considering, and the cheapest answer certainly isn't automatically and always the best. Any good system of food/farming/land use (i.e. agriculture) inevitably entails lots of important and complex questions, and the supermarket system basically decides all these questions strictly on cheapness. Even if a farmer fully recognizes a better way to farm and even if consumers have sufficient agricultural knowledge to be aware of and understand the issues and want to pay for something that would cost even just a penny more per pound, the supermarket model leaves both farmers and consumers pretty much powerless to unite and make those choices. When farmers' profit margins are only pennies or fractions of a penny per pound -- we've read that only about 10% of the average food dollar goes to farmers -- farmers selling to the kind of markets that serve supermarkets can't stay in business doing things that add even a penny to the cost of their product. And most farmers have gotten used to and now take for granted that cheapness is the name of the game. At the other end, consumers are generally far too far removed from agriculture to understand or even hear about most of the decisions that define our agriculture, so, of course, they're powerless to support things they're not aware of or don't really understand. And even if they had the awareness and understanding, there's no way to support a farmer doing something one way when his product is pooled together with all the farmers doing it the other way. And the systems of transporting and processing and packaging and distributing are so extensive and complex that keeping any kind of differentiated product separate is almost always cost prohibitive. In other words, even if it would cost very little for a farmer to make a change on the farm, the cost of keeping that product separate all the way from the farmer through all the middlemen to the consumer is almost always enormous, so any product differentiation (i.e. real consumer choice in farming decisions) is mostly just superficial fluff added on the retail end to mislead consumers (for example, different brand names added to products that are all coming off the same processing line.)

And these decisions compound over time. Traditional foods are forgotten over time. Industrial substitutes become the new normal. Our tastes and preferences are shaped by supermarket shopping habits together with corporate advertizing. And the real richness and quality and integrity of our food supply declines all the while. While we pretend that we're in control as the consumers, buying what we want when we want it, in reality our tastes and preferences grow out of that system, being shaped by that system: we learn to want what the supermarket system wants to feed us.

We hope you can see how everything we've just described operates as a system. And if it's all not a path you're too sure you want to follow, then the question is if and how you can get out of the conundrum. One idea might be to turn to the organic label. We've written more about the organic label before, but we'll just make some brief points here. We definitely think the organic label is preferable to the conventional supermarket system, but we see some severe limitations. First of all, there wouldn't be an organic label at all if it hadn't been for homegrown resistance to the supermarket model, which is how organic agriculture as a distinct alternative came about. Having begun as a defense of homegrown ways and a revolt against the industrial model, can the organic movement now abandon its homegrown ways and trust the supermarket model to be properly constrained by a set of rules? And will the supermarket model of organic not modify and adapt those rules over time to conform (further and worse) to the logic of industrial style agriculture? If homegrown ways of agriculture exposed the need for a distinct alternative to the supermarket model in the first place, will homegrown ways not also be essential to keeping the organic movement honest? And even if the organic rules system operated perfectly, it would still only be a narrowly limited, legalistic system. Organic rules say little or nothing about a majority of the things we question sacrificing for the sake of cheapness (as in the paragraph above.)

So if the organic label isn't worth much apart from the homegrown style of agriculture from which it came, what about farmers at local farmers' markets? If those farmers are also committed to providing a real alternative to the synthetic fertilizers and pesticides and genetic engineering and pharmaceuticals of the supermarket model (which is to say they're practicing the basics of what organic ought to mean), then we think we're starting to talk about significant progress. But we see major limitations in the farmers' market model, too.

On the one side, bureaucrats and lawyers and insurance companies and tax officials, etc., etc. are poised to make selling at farmers' markets too complicated, burdensome, obnoxious, and costly (particularly in terms of both civil and criminal liabilities) for most of the farmers selling at local markets now. The changes that are happening don't bode well for the farmers' market model. Where these pressures aren't squeezing farmers out of the market altogether, they're effectively squeezing them out of local, organic practice, because the farmers are forced to specialize and scale up in ways that practically necessitate non-organic inputs. For example, of all the animal products sold at all the farmers' markets in the whole state, except for all-grass-fed beef -- that leaves all the cheese and dairy, all the eggs, all the poultry, and all the other meats sold at farmers' markets -- we're not aware of any that aren't fed commodity (supermarket style) grain. Many of these same farmers believe in organic principles enough not to use any synthetic fertilizers or pesticides, GMO seed, etc. on their own farms, but their markets force them to specialize and scale up such that they have to depend on outsourcing the growing of feed to farms that represent very different styles of farming from their own. The result, as with other types of food, is that markets fall well short of local, organic potential.

On the other side, relationships between farmers' market customers and farmers aren't deep enough for customers to recognize, value, and support the practices they would choose if they were producing their own food for themselves. Customers lives are busy and full of enough distractions that it takes a concerted effort just to connect with one farm deeply enough to let it begin to affect their supermarket-bred food ways. Spreading those relationships thin by dealing a little bit with one vendor and a little bit with another is a recipe for defaulting to supermarket habits and expectations, largely forcing farmers at farmers' markets to follow them into supermarket style farming. Significant change from the supermarket model will depend on both customers and farmers together changing their food and farming ways.

And that brings us back to the CSA model. The basic idea of our CSA is that it would enable us to farm more like we would if we were growing simply for ourselves instead of conforming our farm to broader market demand (together with all the chemicals and other industrial inputs and shortcuts that make it possible to compete in that market), and on the customer side, our CSA enables our CSA members to be able to eat food more like they would if they were growing for themselves instead of limiting their diets to the kind of food and farming that can compete in the global marketplace. The CSA concept means we try to grow as many different things as we can for our CSA members and they try to eat as many different things from our farm as they can. The idea is that we sell first to them, and they buy first from us. That frees us from catering to less informed customers and allows us to farm in the way we believe best, and it enables those that share our beliefs to obtain and to eat food grown in ways that largely wouldn't be available otherwise.

The opposite of getting food produced by people you know and trust would normally be the kind of food sold in supermarkets. Whether you actually buy it at the supermarket or elsewhere, this is pretty much complete mystery agriculture. You might sometimes have some information about the country of origin, and in those instances you could find out what laws and regulations farmers were supposed to comply with in that country, but even then you're only dealing with extremely limited minimum standards. And since there are so many details you don't know about, and since the farmers really have no means of communicating any of those differentiating details to you, the law of competition pretty much guarantees that all those details will be decided on cost, i.e. the cheapest way to produce that item will prevail. Of course, cheap is a good thing, but there are lots of things that get sacrificed for cheapness, and the supermarket model is pretty helpless to let farmers or consumers make choices about what's worth sacrificing and what isn't. For the sake of cheapness chemical fertilizers are produced from non-renewable sources (mining, fracking, etc.), displacing organic wastes that are now concentrated to the point of pollution in waterways and elsewhere. For the sake of cheapness most of the farm work in our country is structured into jobs that we would never consider fit for any of our own children but only for an immigrant underclass. (Only 18% of farm workers in the US speak English as their first language.) For the sake of cheapness highly erodible soils that ought to be protected by permanent stands of trees and grass are bulldozed and plowed to produce cheap (in the very short term) annual crops. For the sake of cheapness, fruits are picked under-ripe thousand of miles away. For the sake of cheapness pesticides are sprayed on crops that correlate with behavioral and mental disorders in children, contaminate drinking water sources, correlate with higher incidents of cancer, etc. And on top of that, those same pesticides sprayed on one crop destroy honeybee and native pollinator populations, increasing the cost of producing many other crops. (Cheapness often isn't really cheap even in the short run.)

Whole books could be filled and many have detailing these sorts of agricultural issues, but our point here isn't that any of these issues ought to be decided one way or another. Our point is merely that there are questions worth considering, and the cheapest answer certainly isn't automatically and always the best. Any good system of food/farming/land use (i.e. agriculture) inevitably entails lots of important and complex questions, and the supermarket system basically decides all these questions strictly on cheapness. Even if a farmer fully recognizes a better way to farm and even if consumers have sufficient agricultural knowledge to be aware of and understand the issues and want to pay for something that would cost even just a penny more per pound, the supermarket model leaves both farmers and consumers pretty much powerless to unite and make those choices. When farmers' profit margins are only pennies or fractions of a penny per pound -- we've read that only about 10% of the average food dollar goes to farmers -- farmers selling to the kind of markets that serve supermarkets can't stay in business doing things that add even a penny to the cost of their product. And most farmers have gotten used to and now take for granted that cheapness is the name of the game. At the other end, consumers are generally far too far removed from agriculture to understand or even hear about most of the decisions that define our agriculture, so, of course, they're powerless to support things they're not aware of or don't really understand. And even if they had the awareness and understanding, there's no way to support a farmer doing something one way when his product is pooled together with all the farmers doing it the other way. And the systems of transporting and processing and packaging and distributing are so extensive and complex that keeping any kind of differentiated product separate is almost always cost prohibitive. In other words, even if it would cost very little for a farmer to make a change on the farm, the cost of keeping that product separate all the way from the farmer through all the middlemen to the consumer is almost always enormous, so any product differentiation (i.e. real consumer choice in farming decisions) is mostly just superficial fluff added on the retail end to mislead consumers (for example, different brand names added to products that are all coming off the same processing line.)

And these decisions compound over time. Traditional foods are forgotten over time. Industrial substitutes become the new normal. Our tastes and preferences are shaped by supermarket shopping habits together with corporate advertizing. And the real richness and quality and integrity of our food supply declines all the while. While we pretend that we're in control as the consumers, buying what we want when we want it, in reality our tastes and preferences grow out of that system, being shaped by that system: we learn to want what the supermarket system wants to feed us.

We hope you can see how everything we've just described operates as a system. And if it's all not a path you're too sure you want to follow, then the question is if and how you can get out of the conundrum. One idea might be to turn to the organic label. We've written more about the organic label before, but we'll just make some brief points here. We definitely think the organic label is preferable to the conventional supermarket system, but we see some severe limitations. First of all, there wouldn't be an organic label at all if it hadn't been for homegrown resistance to the supermarket model, which is how organic agriculture as a distinct alternative came about. Having begun as a defense of homegrown ways and a revolt against the industrial model, can the organic movement now abandon its homegrown ways and trust the supermarket model to be properly constrained by a set of rules? And will the supermarket model of organic not modify and adapt those rules over time to conform (further and worse) to the logic of industrial style agriculture? If homegrown ways of agriculture exposed the need for a distinct alternative to the supermarket model in the first place, will homegrown ways not also be essential to keeping the organic movement honest? And even if the organic rules system operated perfectly, it would still only be a narrowly limited, legalistic system. Organic rules say little or nothing about a majority of the things we question sacrificing for the sake of cheapness (as in the paragraph above.)

So if the organic label isn't worth much apart from the homegrown style of agriculture from which it came, what about farmers at local farmers' markets? If those farmers are also committed to providing a real alternative to the synthetic fertilizers and pesticides and genetic engineering and pharmaceuticals of the supermarket model (which is to say they're practicing the basics of what organic ought to mean), then we think we're starting to talk about significant progress. But we see major limitations in the farmers' market model, too.

On the one side, bureaucrats and lawyers and insurance companies and tax officials, etc., etc. are poised to make selling at farmers' markets too complicated, burdensome, obnoxious, and costly (particularly in terms of both civil and criminal liabilities) for most of the farmers selling at local markets now. The changes that are happening don't bode well for the farmers' market model. Where these pressures aren't squeezing farmers out of the market altogether, they're effectively squeezing them out of local, organic practice, because the farmers are forced to specialize and scale up in ways that practically necessitate non-organic inputs. For example, of all the animal products sold at all the farmers' markets in the whole state, except for all-grass-fed beef -- that leaves all the cheese and dairy, all the eggs, all the poultry, and all the other meats sold at farmers' markets -- we're not aware of any that aren't fed commodity (supermarket style) grain. Many of these same farmers believe in organic principles enough not to use any synthetic fertilizers or pesticides, GMO seed, etc. on their own farms, but their markets force them to specialize and scale up such that they have to depend on outsourcing the growing of feed to farms that represent very different styles of farming from their own. The result, as with other types of food, is that markets fall well short of local, organic potential.

On the other side, relationships between farmers' market customers and farmers aren't deep enough for customers to recognize, value, and support the practices they would choose if they were producing their own food for themselves. Customers lives are busy and full of enough distractions that it takes a concerted effort just to connect with one farm deeply enough to let it begin to affect their supermarket-bred food ways. Spreading those relationships thin by dealing a little bit with one vendor and a little bit with another is a recipe for defaulting to supermarket habits and expectations, largely forcing farmers at farmers' markets to follow them into supermarket style farming. Significant change from the supermarket model will depend on both customers and farmers together changing their food and farming ways.

And that brings us back to the CSA model. The basic idea of our CSA is that it would enable us to farm more like we would if we were growing simply for ourselves instead of conforming our farm to broader market demand (together with all the chemicals and other industrial inputs and shortcuts that make it possible to compete in that market), and on the customer side, our CSA enables our CSA members to be able to eat food more like they would if they were growing for themselves instead of limiting their diets to the kind of food and farming that can compete in the global marketplace. The CSA concept means we try to grow as many different things as we can for our CSA members and they try to eat as many different things from our farm as they can. The idea is that we sell first to them, and they buy first from us. That frees us from catering to less informed customers and allows us to farm in the way we believe best, and it enables those that share our beliefs to obtain and to eat food grown in ways that largely wouldn't be available otherwise.

Monday, October 13, 2014

Putting up the harvest

|

| Persimmons |

|

| Pulping the persimmons |

|

| Just one more step to persimmon pudding! |

|

| Processing roselle for drying or sauce |

|

| What to do with an abundance of eggplant? Peel, slice, and roast with salt and garlic. Freeze. Use in casseroles or on pizza. |

|

| We're having a great pumpkin year. For the ones that don't seem to be keeping we've been canning the pulp. |

Saturday, October 11, 2014

Wednesday, August 6, 2014

Farm tour

|

| Chicks taking a ride on mother hen |

|

| Can you name these plants - close ups and ID below. |

|

| The first roselle (hibiscus) is almost ready to harvest. |

|

| Sesame in flower |

|

| Pearl millet |

|

| If possible we try to leave volunteer plants in the garden - a beautiful volunteer butternut. |

|

| Summer peas - zipper cream |

|

| Overgrown beans - on purpose to save seed! |

|

| Tulsi basil makes great tea! |

|

| Buckwheat - hoping to hand harvest enough for pancakes. |

|

| Another volunteer - husk cherries, which I'm thankful for since none of the ones I tried to grow germinated! |

|

| It's been an incredible squash year - don't be tired of it yet - the season will eventually come to an end. |

|

| We've had at least a couple different critters find our cantaloupes this year. |

|

| Looks like lots of tomatoes still to come - we'll see how long they last. |

|

| Reusing the cucumber trellis for a late planting of a climbing type summer pea - red rippers. |

|

| New to us this year - red noodles - a yard long "bean" |

|

| The start of fall - germinating radishes |

|

| A wall of beans |

|

| Basil, basil, pesto, pesto! |

|

| New to us this year - New Zealand spinach |

|

| And to think it all started with a tiny, tiny seed this spring. Amazing! |

|

| Who wants just normal zinnias? Stripey |

|

| Not a great photo - summer spinach (malabar spinach) climbing what was our sugar snap trellis |

|

| Red stockton onion seed ready to harvest |

|

| If we don't get any sweet potatoes this year, we hope to at least get some sweet potato fed deer meat! |

|

| New to us - Trombocino - gone too far to save seed |

|

| Japanese beetles have been terrible this year but no major crop losses |

|

| New to us - edamame - mainly to multiply out the seed this year |

|

| Did you know cattle don't have front top teeth? Paul doesn't either at the moment! |

Wednesday, July 30, 2014

Tuesday, July 29, 2014

Corn Workshop

If the last couple generations of losing our local food culture and

falling into corporate-industrial food ways have left you, as most of

your peers and neighbors, not really knowing (or having forgotten) how

to make use of and enjoy our region's most basic, traditional food

staple, then plan to come to our corn workshop! (We're talking about

field corn/dry corn as in cornmeal, grits, or hominy; sweet corn was

pretty much unheard of in our region when our grandparents were growing

up, and the equivalent roasting ear corn filled the roll of a seasonal

vegetable, not the year-round staple grain.) We'll show you how to

prepare and enjoy a variety of staple foods to include throughout your

week, partly as main meals, but mainly as a foundational starch to go

with other foods in the way that pasta, rice, boxed breakfast cereals,

etc. have largely replaced.

We're planning the workshop for two weeks from today, Tuesday, August 12 at 6pm. The workshop will be free with a $40 advance purchase of cornmeal and/or grits and/or whole kernel corn for hominy/tortillas... We're about out of cornmeal and grits now, but we'll have a fresh supply from the mill at our first-week-back-from-the-mill discounted price by the time of the workshop. We won't have a complete meal for you, but we'll have samples of everything, so come hungry. If you're interested in coming, you can pre-pay for your corn products at the farmers' market either this week or next. Workshop size will be limited -- our kitchen is fairly small -- so if we reach our limit we'll have to cut things off there. It would be nice to hear from you now if you're interested.

We're planning the workshop for two weeks from today, Tuesday, August 12 at 6pm. The workshop will be free with a $40 advance purchase of cornmeal and/or grits and/or whole kernel corn for hominy/tortillas... We're about out of cornmeal and grits now, but we'll have a fresh supply from the mill at our first-week-back-from-the-mill discounted price by the time of the workshop. We won't have a complete meal for you, but we'll have samples of everything, so come hungry. If you're interested in coming, you can pre-pay for your corn products at the farmers' market either this week or next. Workshop size will be limited -- our kitchen is fairly small -- so if we reach our limit we'll have to cut things off there. It would be nice to hear from you now if you're interested.

Monday, July 28, 2014

Tomato time

Monday, July 7, 2014

Thursday, June 26, 2014

Wheat harvest

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)